Jupiter comet’s water matches Earth’s oceans, may have brought water to globe: NASA

Jupiter comet’s water matches Earth’s oceans, may have brought water to globe: NASA

Comet 67P’s water has the same molecular signature as Earth’s oceans, suggesting it may have contributed to Earth’s water supply.

Full Article

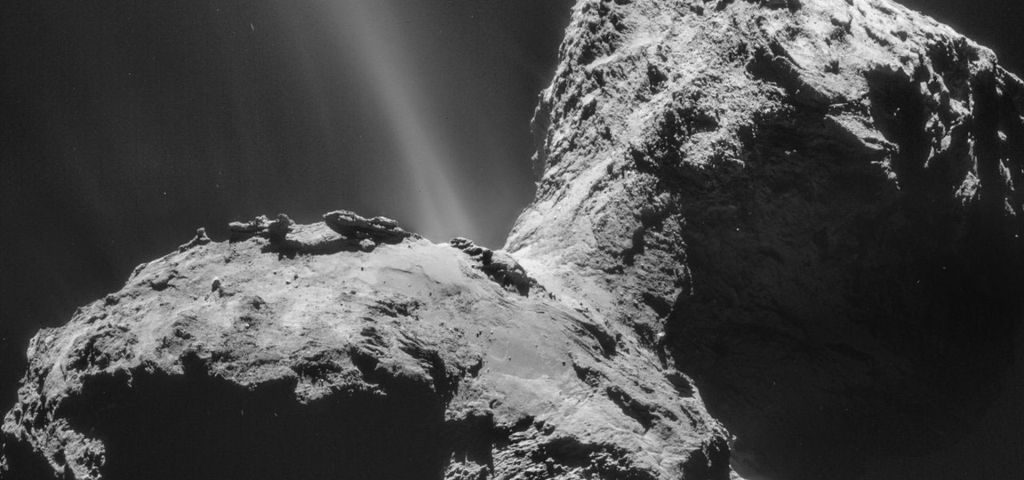

a day ago a day ago 2 days ago 2 days ago 2 days ago 2 days ago 2 days ago 3 days ago 3 days ago 3 days ago 21 minutes ago 39 minutes ago 44 minutes ago an hour ago an hour ago 2 hours ago 2 hours ago 2 hours ago 3 hours ago 3 hours ago The connection between asteroid water and Earth’s oceans is generally well-supported, but the role of comets remains uncertain. Kapil Kajal Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on Jan. 31, 2015. NASA New research indicates that the water on Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko has a molecular signature closely matching that of water found in Earth’s oceans. This discovery revives the possibility that Jupiter-family comets like 67P played a role in supplying water to our planet, countering previous studies that questioned this connection. Water is fundamental to life on Earth. While some of it likely came from the gas and dust that formed our planet approximately 4.6 billion years ago, the intense heat from the young Sun would have vaporized much of that initial water. How Earth became abundant in liquid water has long been a scientific debate. Researchers have proposed that part of Earth’s water was produced by volcanic activity. Water vapor released by volcanoes eventually condensed and fell as rain, contributing to our oceans. Additionally, evidence suggests that a significant proportion of Earth’s oceans was derived from icy bodies like asteroids and possibly comets that collided with our planet during the early years of the solar system. This period, marked by a barrage of impacts four billion years ago, could have facilitated water delivery to Earth. The connection between asteroid water and Earth’s oceans is generally well-supported, but the role of comets remains uncertain. Previous measurements of Jupiter-family comets revealed a strong link between their water and Earth’s based on a crucial molecular signature. This signature is the ratio of deuterium (D) to regular hydrogen (H) found in water, offering insights into where these bodies formed in the solar system. Deuterium is a heavier form of hydrogen, and its concentration varies based on an object’s distance from the Sun. Comets, forming in the cold outer solar system, tend to have higher deuterium levels than asteroids, which form closer to the Sun. Over the last two decades, water vapor measurements in several Jupiter-family comets indicated deuterium levels similar to those found in Earth’s water, suggesting a potential connection in water delivery to Earth. Kathleen Mandt, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, led a new study published in Science Advances that reevaluated the deuterium abundance in Comet 67P. “It was starting to look like these comets played a major role in delivering water to Earth,” Mandt noted. However, in 2014, the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission to 67P presented a new challenge to this theory. Analysis of Rosetta’s water measurements revealed that 67P contained the highest concentration of deuterium found in any comet—roughly three times higher than in Earth’s oceans. This discovery led scientists, including Mandt, to rethink the idea that Jupiter family comets contributed to Earth’s water reservoir. To further investigate the deuterium levels in 67P, Mandt’s team utilized an advanced statistical technique to analyze over 16,000 measurements taken by Rosetta. They aimed to understand why different hydrogen isotope ratios were observed in comet water. Laboratory experiments and previous observations suggested that dust surrounding comets could influence the deuterium readings. Mandt expressed her curiosity, stating, “I was just curious if we could find evidence for that happening at 67P.” Remarkably, her team did find a correlation between deuterium measurements and the amount of dust in the comet’s coma—the cloud of gas and dust surrounding it. This connection revealed that some measurements taken near the spacecraft might need to reflect the comet’s true water composition accurately. As a comet travels closer to the Sun, its surface heats up, causing it to release gas and dust. Studies indicate that deuterium-rich water tends to bind to dust grains more than regular water, which could lead to misleadingly high deuterium readings in the coma. When the dust reaches the outer coma, it dries out, losing deuterium-rich water, allowing for accurate measurement of the comet’s true deuterium content. These findings could have significant implications for understanding the origins of Earth’s water and how comets contribute to this vital resource. Mandt and her team believe that this research might change the narrative regarding water sources on our planet, reopening discussions about the role of comets in Earth’s water history. Stay up-to-date on engineering, tech, space, and science news with The Blueprint. By clicking sign up, you confirm that you accept this site’s Terms of Use and Privacy Policy Kapil Kajal Kapil Kajal is an award-winning journalist with a diverse portfolio spanning defense, politics, technology, crime, environment, human rights, and foreign policy. His work has been featured in publications such as Janes, National Geographic, Al Jazeera, Rest of World, Mongabay, and Nikkei. Kapil holds a dual bachelor’s degree in Electrical, Electronics, and Communication Engineering and a master’s diploma in journalism from the Institute of Journalism and New Media in Bangalore. a day ago a day ago a day ago a day ago